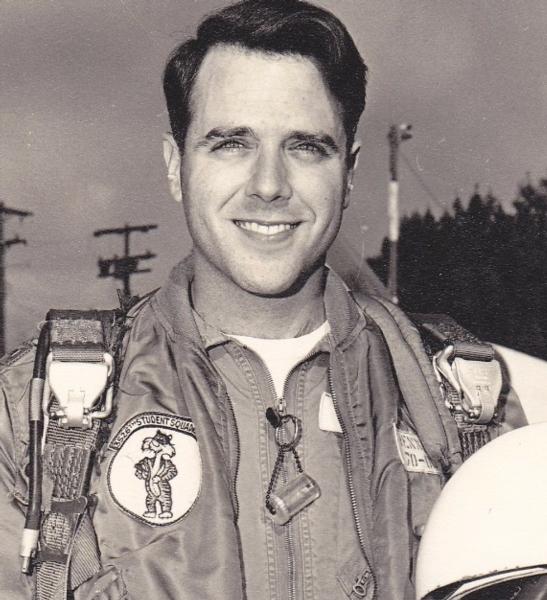

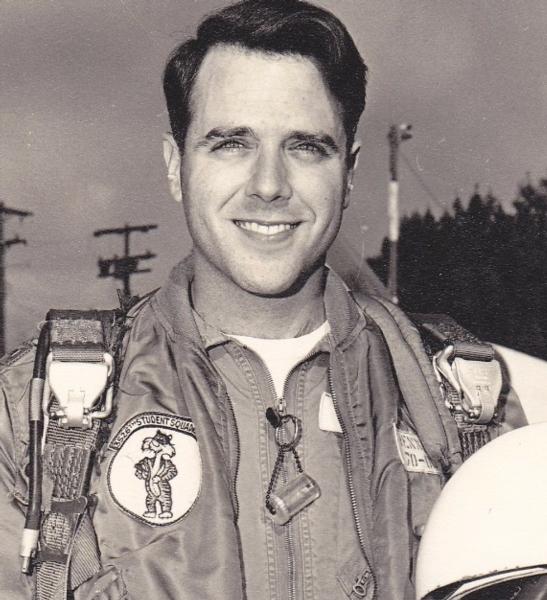

- Buddy Bennett went missing in Vietnam 52 years ago on his 30th birthday, leaving a hole in his Mississippi family’s lives. Ray Nothstine spoke to his sister in the lead up to Memorial Day about their experience.

Thomas W. “Buddy” Bennett has a headstone in Natchez National Cemetery but there is no body there.

“We love you son,” reads a portion of the stone.

None of his surviving family has any idea where Bennett might be since turning 30 on December 22, 1972. The same day he went missing. Bennett’s now been MIA for 52 years — remains unrecovered. Whereabouts unknown.

Jane Skelton, one of Buddy’s sisters, lives in Greenville, Mississippi. She says he wrote home before the fateful mission saying, “I’ll be back in time at the base [in Thailand] to see Bob Hope’s show.”

Operation Linebacker II was the “shock and awe” bombing meant to end America’s eight-year direct combat involvement in Vietnam. President Richard Nixon wanted to force North Vietnam back to the negotiating table at the Paris Peace Accords.

Nixon promised to end the conflict and bring home the nearly 600 American prisoners of war still held in and around Hanoi.

His answer was a massive wave of B-52s flying bombing missions over Hanoi and Haiphong out of Guam and U-Tapao Air Base in Thailand. Almost every old rule of off-limits targets were finally taken off the table.

The largest arsenal of heavy bombers since World War II, Linebacker II became known as “The Christmas Bombings” because it occurred in late December.

Flying over North Vietnam was undoubtedly dangerous. Most historians agree it was the most heavily defended airspace in the world at the time. The North Vietnamese had advanced Soviet surface-to-air missiles that could shoot down America’s best fighters and bombers.

Complicating matters the missions were planned from Strategic Air Command headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base near Omaha, Nebraska. The plan called for B-52 waves to arrive flying identical approach patterns, making it easier for SAM crews to predict the flight angles despite American jamming technology on B-52s and the skills of F-4C Wild Weasel pilots striking enemy missile sites.

Fifteen B-52s were shot down and 33 crew members were killed in action over the 11 days. B-52 flight tactics were later adjusted, saving more aircrew lives.

Not only was Bennett’s crew blown from the sky on December 22, but former NFL star Derrick Thomas’s father was killed when his B-52 was shot down a few days earlier.

Three men from Buddy’s crew were taken prisoner, survived, and were repatriated during Operation Homecoming in 1973.

According to Bennett’s sister, the tail gunner said he saw five parachutes deploy on a moonlit night. The tail gunner being the last to bail out made six, which meant the entire crew ejected from the aircraft.

It is believed that Buddy made the mayday call after the B-52 was struck by the SAM. “I’ve heard that tape,” says Skelton. “It was Buddy. It was Buddy’s voice on the mayday call. I don’t know where that recording is anymore, but it was Buddy’s voice on the mayday.”

Buddy, the co-pilot on that mission, was given a presumption of death finding by the U.S. government in 1980 along with two other crewmates. Buddy was promoted to the rank of major. The remains of Gerald W. Alley and Joseph B. Copack, two of Buddy’s crewmates, were recovered and sent home in June of 1989.

“They have found nothing from Buddy,” says Skelton. “They have not found a shred of his flight suit. Nothing. We’ve given DNA. We’ve done all that.” The Air Force still sends the surviving family messages and Skelton says they are still working on a recovery.

Bennett, a graduate of the University of Southern Mississippi, has scholarships in his name and a professorship chair named after him. He was attending seminary in Georgia and planning on being a Presbyterian minister when he left to become an Air Force pilot.

“Buddy had a passion to fly,” declares Skelton. “He loved to build model airplanes. He put all kinds of model airplanes together and hung them from the ceiling.” She called him the perfect southern gentleman, adding that “Buddy was just like his daddy.”

“Daddy and I thought he was still alive,” says Skelton. We were optimists.” Skelton says her mom said she knew she’d never see him again.

“My grandmother lost her first-born son, and my mother lost her first-born son and that had a negative impact on my mom,” says Skelton.

Buddy’s uncle lost his life in 1942 when the plane he was flying crashed near Puerto Rico, where he was stationed during World War II.

I asked Skelton what it has been like for her family not having closure about Buddy, not knowing what happened to him. She paused for a moment and quoted William Tecumseh Sherman, “War is hell.”

Then she added, “We are all so proud of Buddy. He volunteered. Buddy volunteered for the Marines and then the Air Force. He helped free those prisoners of war who were languishing over there.

“Buddy was an Eagle Scout, too,” says Skelton. “He had that honor God and country commitment throughout his entire life.”

Buddy was tall at six foot four inches. Skelton said she looked up to him literally and figuratively.

“Sometimes a B-52 will be flying above me, particularly when I’m near or around Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. I’ll just pause and look up, watching it and Buddy comes right to my mind.”

“It’s a beautiful plane,” she adds.

Bennett’s marker is one row over from his parents. His dad, a World War II veteran passed away in 2001 and his mother in 2011.

A Christian family, Skelton says, “I’m so glad mom and daddy now know everything that happened to Buddy. He’s no longer lost to them.”

Read original article by clicking here.