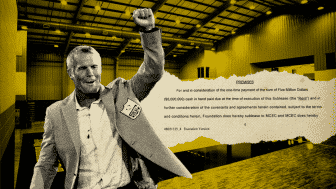

Former NFL quarterback Brett Favre had a way with Mississippi government officials.

Whether the football star was looking for funds to boost a startup company that he thought would make him rich or angling to take credit for building a new volleyball stadium at his alma mater, Favre knew he could count on Mississippi’s governor, the state’s welfare chief and a grant-funded nonprofit director to help him out.

He wasn’t shy about sweetening the deal for others or trading on his own fame and connections to secure a financial bailout. Favre, the Hall of Fame quarterback and home-state hero, had special access to Gov. Phil Bryant and people who controlled the state’s welfare spending.

Read Part 1: Phil Bryant had his sights on a payout as welfare funds flowed to Brett Favre

Favre said a nonprofit director Nancy New gave him $5 million in grant funds to build a volleyball stadium at University of Southern Mississippi – a payment that could be part of forthcoming civil litigation. A pharmaceutical company Favre backed, called Prevacus, also ended up receiving $2.15 million in allegedly stolen funds from the Mississippi Department of Human Services. The quarterback collected an additional $1.1 million welfare dollars personally.

In the course of his dealings on behalf of Prevacus or the volleyball stadium, Favre proposed the following:

- Give then-Gov. Phil Bryant shares in Prevacus, or transfer his own personal shares to the governor

- Give nonprofit founder Nancy New shares in Prevacus

- Buy then-MDHS director John Davis a F-150 Raptor — Ford’s top-of-the-line pickup truck

- Convince New and Davis to pay off more than $1 million he owed on the volleyball facility

- Ask the governor for a meeting with the replacement MDHS director for more volleyball money

- Convince USM to finance Prevacus in exchange for stock for himself

- Aim to take home $20 million

Favre’s efforts to entice a welfare contractor with stock in Prevacus — which are central to embezzlement charges against Nancy New and her son, Zach New — are among the revelations of Mississippi Today’s investigative series, “The Backchannel.”

Discourse around the welfare scandal has been at times hyper focused on the fact that the money that officials misspent came from a federal program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, known for providing the welfare check. Many recipients of the funds have said they would have never knowingly taken money from the poor. But the narrow lens on TANF in the case of Prevacus ignores the reality that almost all the federal grants Mississippi Department of Human Services administers have to do with protecting the vulnerable – and there’s no scenario where it’s proper for MDHS grant money to flow to a private business outside the view of the public.

With the drug company investment, the volleyball arena and other payouts, at least $8 million in misspending auditors identified within Mississippi’s larger welfare scandal stemmed from Favre’s requests or fees. New’s nonprofit, called Mississippi Community Education Center and primarily funded by MDHS, directly paid Favre more than $1 million to be a spokesman for the Families First for Mississippi program. He’s since returned those funds, but the auditor says Favre still owes $228,000 in interest on the money he improperly received. Current MDHS Director Bob Anderson said last October that the department would be filing civil charges against Favre along with many others, but is awaiting approval from the attorney general.

While Favre has said he didn’t know the funding he received was from a program that is supposed to help the poor, text messages obtained by Mississippi Today show he knew he was dealing in government grants. Favre has not been accused of a crime within the scheme and declined to interview with Mississippi Today.

Below is a breakdown of Favre’s dealings with Mississippi officials and welfare-funded projects. Mississippi Today has reviewed hundreds of pages of written communication, which are reprinted here exactly as they appear without correction.

Give then-Gov. Phil Bryant shares in Prevacus

At the very start of their discussions with the governor, Favre and his business partner, Florida neuroscientist and Prevacus owner Jake Vanlandingham, suggested motivating Bryant to lend his support by giving him shares in the company, which said it was developing medication to deal with concussions.

Vanlandingham, who himself suffered severe brain injury as a young man, has worked since 2012 on finding a solution to the concussion crisis. He told Mississippi Today his priority is to prevent brain damage and save lives, but like any startup, he needed capital to realize his vision – and it was common for him to offer company incentives in exchange for the help of influential figures.

“I guess we verbally ask the Governor what the rules are to compensate him,” Vanlandingham texted Favre in late 2018. “Worse case scenario I give you more stock that as an individual u can transfer to him. But let’s avoid trouble at all cost.”

Favre later wrote, “Group text the governor and tell him we want to give him shares but don’t want to get anyone in trouble.”

The athlete and scientist had talked like this for years, brainstorming potential partners. Bryant eventually agreed by text to accept a company package two days after he left office, Mississippi Today first reported. Bryant denied that he was ever going to take stock in the company, despite text messages that show he continued to discuss a business deal with Vanlandingham until arrests derailed the arrangement.

Give Nancy New shares in Prevacus

Two days after their first meeting with the governor, Favre sent the contact information for Nancy New and told the scientist to reach out to her. “Offer her whatever you feel like,” Favre wrote.

After Vanlandingham’s first conversation with New, Favre asked, “Did you and Nancy discuss shares or commission?”

“We did briefly. She was all about it but graceful in saying she loved the cause and how much it could help kids. She has 4 grandkids,” the scientist said.

“I figured that if you mentioned it most likely she would refuse. I believe if it’s possible she and John Davis would use federal grant money for Prevacus,” Favre said.

Directly after their meeting with New and Davis at Favre’s house, Vanlandingham texted New to say that he would like to give her 50,000 shares in his company, according to documents attached to a state court filing. She said she would have helped him regardless, but thanked him for the gesture.

Vandlandingham relayed this exchange to Favre, who responded, “Hell we giving her something.”

“I’ll slip it to her,” the scientist wrote.

New began paying Prevacus a couple weeks later in late January of 2019, the indictment against her alleges. Two months after that, Vanlandingham updated Favre on the status of New’s ownership in the company.

“Nancy did get approval now to take 50k in shares from Prevacus. I gave her the good shares that won’t cost her or have a tax requirement,” the scientist wrote.

“Now that’s awesome,” Favre said.

Prosecutors have accused New of embezzlement for allegedly paying $2.15 million in welfare money to Prevacus and its affiliate company PreSolMD in exchange for personal stock, among several other charges, and could face hundreds of years in prison.

Buy John Davis a F-150 Raptor

After first connecting with New, Vanlandingham texted Favre to ask if he knew John Davis, the director of Mississippi Department of Human Services, the New nonprofit’s primary source of funding.

“Yep. He is just like her,” Favre wrote.

Favre was in direct communication with Davis. The welfare director texted the athlete on Easter in 2019 to thank him for his friendship.

“John thank you very much and I am very proud to call you my friend!!! Have a wonderful blessed day,” Favre responded.

The week Prevacus was supposed to receive its first round of funding from New, Favre texted his partner: “This all works out we need to buy her and John Davis surprise him with a vehicle I thought maybe John Davis we could get him a raptor.”

Minutes later, Favre followed up: “Honestly give me your thoughts on what you think all this means … When we will make money.”

Get New and Davis to pay off a $1.1 million debt

Around the same time, Favre was getting nervous about holding the bag for more than $1 million that the Southern Miss Athletic Foundation needed to build the new volleyball facility Favre promoted.

“Hey brother Deanna and still owe 1.1 million on Vball,” Favre texted Davis, referring to his wife, Deanna Favre. “Any chance you and Nancy can help with that? They don’t need it at the moment.”

“You and Nancy stuck your neck out for me with jake and Prevacus I know and that’s going to turn out very good I believe,” he added.

“Good to hear from you. Let me see what we can do,” Davis responded. We certainly want to see the VBall project come together. I’ll get back with you tomorrow.

“We value you Brett and are willing to always be supportive. Did not look at it as sticking our neck out as much as helping a friend and potentially many many more who are in need if treatment,” the welfare director added.

But as the auditor was about to launch an investigation into Davis’ department, grant funding was up in the air.

“I still owe 1.2 for the Vball complex on campus and not sure if Nancy and John can keep covering for me,” Favre texted his business partner.

The volleyball money never came.

A couple months later in July, Favre texted Vanlandingham: “Here is my dilemma which isn’t your concern. Nancy has been awesome to me and has paid 4.5 million for a 7 million dollar facility. And she said it was all gonna be taken care of until this morning. Suddenly she said I don’t think I can do anymore. So now I am looking at a big pay out.”

New, a USM alumnus, sat on the athletic foundation’s board. Davis also graduated from the university.

Ask the governor for a meeting with the replacement MDHS director for more volleyball money

Bryant kicked Davis out of office in late June when an MDHS employee alerted the governor to a small instance of alleged fraud by the director. When Bryant’s new director Christopher Freeze came in, Favre convinced the governor to hold a meeting so he and New could ask Freeze about more funding for their project, Freeze told Mississippi Today.

Bryant recalled that they were discussing the volleyball center. Freeze said he told them, “No,” and that the department had reinstituted a bidding process for TANF funds, which hadn’t happened since Bryant’s first year in office.

Once Vanlandingham got word that Davis had left MDHS, he asked Favre what the new director was like, and the quarterback responded, “Nancy said he ain’t our type.” The scientist quipped that they may need the governor “to make him our type.”

After the arrests, Vanlandingham texted Favre that he thought the investor they were close to securing was going to fall through, and that he was trying to scrape funds together to keep the drug development on track. Favre said he couldn’t help.

“I would but up to my eyeballs in vball debt,” Favre texted on February 11, 2020, six days after the auditor arrested Davis and New under indictments naming Prevacus.

Days earlier, The Associated Press quoted Favre saying that he raised the funds to build the volleyball center.

“We wanted to do something for a high school and (Southern Miss),” he told the AP. “…And for Southern Miss, that was difficult — it’s hard to get people to donate for volleyball. But we’ll be opening an $8 million facility that will be as good as any in the country at Southern Mississippi.”

“One of the things I am most proud of about all the things I have been able to achieve is being able to give away so much money and help so many people with Favre4Hope,” he added. “Special Olympics, Cystic Fibrosis, Make-A-Wish Foundation, a big chunk of money to the Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis, to St. Jude and to Ronald McDonald House.”

“It would be a shame if people who can help don’t help. By no means are we perfect, but we do try to give back,” Favre said.

Convince USM to finance Prevacus in exchange for stock for himself

In 2017, several months before New sent $5 million to Southern Miss Athletic Foundation for the volleyball building, Vanlandingham suggested approaching USM to finance Prevacus.

“I mean if you and him for example can get USM to put up 3.5M you’d be able to earn 280k in either stock/cash or a combo,” Vanlandingham texted Favre.

“If it passes the smell test I can get them to put the money up!!” Favre responded.

In late 2018, after they brought Bryant in, they revisited the prospect of working with Southern Miss.

“I guess between you, her and the governor we can get southern miss to work with us on prevacus project. We will give southern miss a good patent royalty position so when the drug gets approved they will make many many millions,” Vanlandingham texted Favre two days after their meeting with the governor in late 2018.

Aim to take home $20 million

Favre and Vanlandingham, a neuroscientist from Florida, spoke frequently for years, texts show, about how much money they stood to make if only they could get their concussion treatment drug through human trials and FDA approval.

Previously, Favre had similarly pushed an expensive new compounded pain cream that the FBI later investigated, uncovering a more than $515 million health insurance fraud scheme based in Mississippi that led to at least 20 convictions, Hattiesburg American reported. Officials did not accuse Favre of a crime within the scandal.

When Prevacus started engaging Favre, concussions were a hot button issue in the NFL at the time, and the star quarterback was not only an obvious choice as a sponsor for Prevacus, but an aspiring businessman eager to capitalize on the phenomenon.

“Call me crazy but my goal is to take home 20 million when it’s all said and done,” Favre texted Vanlandingham in 2018.

Another time, Favre asked, “And it doesn’t have to pass fda approval to make money correct?”

The scientist texted Favre grand promises of financial returns, but also attempted to manage the athlete’s expectation in dry banter.

“If phase 1 kills people we are done,” Vanlandingham texted Favre in 2019, a few weeks after receiving its first payment from New, “if it’s safe we move on and raise the next money.”

This is a supplement to Part 1 in Mississippi Today’s series “The Backchannel,” which examines former Gov. Phil Bryant’s role in the running of his welfare department, which perpetuated what officials have called the largest public embezzlement scheme in state history.

The post ‘You stuck your neck out for me’: Brett Favre used fame and favors to pull welfare dollars appeared first on Mississippi Today.