Gulfport, Miss. – A Charleston, South Carolina man pleaded guilty to being a felon in possession of a firearm.

Kiln Man Pleads Guilty to COVID-Related Wire Fraud

Gulfport, Miss. – A Kiln, Mississippi man pled guilty to wire fraud related to the COVID pandemic.

Pair of Former Volunteer Fire Department Employees Guilty of Embezzlement

JACKSON, Miss. –Today State Auditor Shad White announced both Mark Hanna and Linda Mannon have been convicted of embezzlement in Marshall County Circuit Court. The case was prosecuted by District Attorney Ben Creekmore’s office in Judge Kent Smith’s court chambers. The guilty plea and sentencing were recorded last week.

“Unfortunately this is one of several cases my team has cracked involving funds that should have been spent on fire department services,” said Auditor White. “Putting a stop to this kind of theft is important because those dollars should be spent on more fire protection for the firefighters and citizens. Thank you to our great investigators who worked this case.”

Mark Hanna and Linda Mannon were arrested in October 2021 after being indicted for embezzling over $35,000 from the Red Banks Volunteer Fire Department (RBVFD). Mark Hanna is the former RBVFD Chief, and Mannon worked as a secretary for the fire department. The pair embezzled both equipment and money from the volunteer fire department.

Both Mark Hanna and Linda Mannon are now convicted of a felony offense and will not be able to handle public money again. Judge Smith’s sentencing order has been filed with the Marshall County Circuit Clerk’s office.

Suspected fraud can be reported to the Auditor’s office online any time by clicking the red button at www.osa.ms.gov or via telephone during normal business hours at 1-(800)-321-1275.

The post Pair of Former Volunteer Fire Department Employees Guilty of Embezzlement appeared first on Mississippi Office of the State Auditor News.

Former State Hospital Police Officer Arrested for Fraud, Extradited from Texas

JACKSON, Miss. – Today State Auditor Shad White announced former Mississippi State Hospital Police Department officer Roberto Williams has been arrested in Texas and extradited back to Mississippi after he was indicted for fraud by a Rankin County grand jury. Special Agents presented a $3,135.62 demand letter to Williams. The demand amount includes interest and investigative expenses.

Williams is accused of submitting fraudulent timesheets to receive payment for time he was not actually working. He allegedly left work for extended periods of time while he was “clocked in” and being paid by the police department. Williams’s purported scheme took place in 2020 from April to June – soon after he was hired. Officials from the Mississippi State Hospital Police Department contacted the Auditor’s office after noticing discrepancies in Williams’s timesheets.

“I want to thank District Attorney Bramlett, the investigators in the Office of the State Auditor, and all the other law enforcement officers who worked on this case,” said Auditor White. “We are committed to working together to safeguard public money.”

Williams was arrested in late January by the Navarro College Department of Public Safety with assistance from the Lancaster Police Department. He was transported back to Mississippi by the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department. Bail will be set by the court.

If convicted, Williams faces up to 5 years in prison or $10,000 in fines. All persons arrested by the Mississippi Office of the State Auditor are presumed innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. The case will be prosecuted by the office of District Attorney John Bramlett.

No surety bond covers Williams’s employment as a police officer at the Mississippi State Hospital. Surety bonds are similar to insurance designed to protect taxpayers from corruption. Williams will remain liable for the full amount of the demand in addition to criminal proceedings.

Suspected fraud can be reported to the Auditor’s office online any time by clicking the red button at www.osa.ms.gov or via telephone during normal business hours at 1-(800)-321-1275.

The post Former State Hospital Police Officer Arrested for Fraud, Extradited from Texas appeared first on Mississippi Office of the State Auditor News.

Photo gallery: Equestrian program at Mississippi College

Mississippi College student Sydney Pace, 18, has been riding horses since she was 9 years old. At 4 feet 11 inches tall, the Oxford native has become an expert at handling horses vastly larger than herself.

A psychology major, Pace said it’s long been a goal to join the riding team at Mississippi College. Established in 2007, the equestrian program operates at Providence Hill Farm in Hinds County. However, with the recent loss of the team’s coach, there is currently no team in place. This means students don’t compete in competitions, but Pace and other riders at the college do earn a physical education credit. She still rides for the enjoyment, and for her love of horses.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Read original article by clicking here.

Former Hattiesburg News Editor Admitted to Defrauding Employer of $288,228.00

It’s been just over a year since David Gustafson suddenly, but gracefully, resigned as editor and publisher of The Pine Belt News, Hub City Spokes and other local publications. Now we know why.

Circuit Court documents filed from March – May of 2021 indicate that Gustafson has admitted to violating his fiduciary responsibilities and the trust of his employer, Hattiesburg Publishing, Inc., by taking at least $288,228 for his own benefit.

He did so by carrying out several unauthorized financial transactions: writing single-signature checks, using the company’s credit cards and PayPal account, and helping himself to cash. He also hid, withheld, and misrepresented information and documents to prevent Hattiesburg Publishing from discovering his unauthorized financial activities.

However, Hattiesburg Publishing did discover his fraudulent activities and filed a complaint in Circuit Court this past March.

A LITTLE BACKGROUND

During his almost 11-year tenure, Gustafson acquired a reputation in the Pine Belt as a respected, community-oriented journalist. He oversaw the award-winning work of staffers at the Lamar Times, the Petal News, Camp Shelby Reveille, the Hattiesburg Post, Signature Magazine and Pine Belt Sports. He and his staff originated the well-known Best of the Pine Belt Award Show.

In his July 1, 2020 final column, Gustafson outlined the growth of the organization’s publications, the awards they won and the roles they play in the Pine Belt community. He thanked readers for their patience, grace, friendship and support.

“As for me, I can’t reveal what my future plans are quite yet, but I’m looking forward to continuing my work as a writer and a storyteller, and I’m looking forward to contributing in new, meaningful ways,” he wrote. “And most of all, I look forward to doing it right here in the Hub City. I’m an Okie by birth and a Mississippian by choice.”

PAYBACK REALLY IS HELL

As of March 2021, when the complaint was filed, Gustafson had repaid Hattiesburg Publishing $168,000. Of that amount, $120,000 was in paychecks Gustafson had not cashed and the remaining $48,000 was from his 401K.

The complaint notes that Gustafson still owes $120,220. It also asks for a punitive judgment of treble that amount: Hattiesburg Publishing stated that it continues to incur financial losses due to attorneys’ fees, loss of interest, remedial business loss, and interest. (The request was later amended to ask repayment of $120,228, as well as $40,076 for attorneys’ fees and another $120,228 in punitive relief.)

A summons was delivered to Gustafson March 11, 2021, requiring written response to the complaint within 30 days. He did not respond, and Hattiesburg Publishing requested an entry of default April 1, 2021. The entry of default is dated April 15.

Hattiesburg Publishing filed a motion for default judgment April 23, 2021. The document notes that Gustafson has admitted legal liability and guilt for fraud, breach of fiduciary duties, theft and/or conversion, and other charges. It also states that Gustafson has admitted legal liability for the actual, compensatory, consequential, and punitive damages described in the complaint.

The motion requests a total of $280,532 plus all applicable interest and court fees.

The Hon. Robert B. Helfrich considered the motion and all applicable materials before signing the final judgment on April 30, 2021. His findings, as listed in the final judgment:

- Defendant David Gustafson is in default and has thus admitted all allegations of the Complaint, including the allegations of fraud and breach of fiduciary duties.

- Actual loss damages of Plaintiff are assessed and awarded in the specified amount of $120,228.

- Punitive damages against Defendant are assessed and awarded in the specified compromised prayer amount of $120,228.

- Attorneys’ fees are assessed and awarded in the amount of $40,076.

Helfrich’s final judgment was filed May 3, 2021; it awards Hattiesburg Publishing, Inc., $280,532 plus applicable interest and court fees.

HPNM reached out earlier this week to Wyatt Emmerich, director and president of Hattiesburg Publishing, Inc. Emmerich stated that he has no comment on this matter.

gustafson order-converted-compressedgustafson-compressed

TRUMP’S CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORMS BRING EARLY RELEASE FOR BOLTON

Former Forrest County Chief Deputy Charles Bolton has been released eight months early under The First Step Act, the criminal justice reform legislation that President Trump signed into law in December 2018.

Bolton was released just before Thanksgiving to a federal halfway house here. Under the terms of his original sentence, which included a 12-month enhancement for food theft, he would have served until July 2020. HPNM has not yet learned how long Bolton will spend at the halfway house.

Trump was quoted by Vox.com earlier this year as saying that previous sentencing laws have harmed the African-American community “wrongly and disproportionately,” and that the First Step Act offers redemption by allowing nonviolent offenders to reenter society as productive citizens. The act affects only the federal prison system, which involves about 181,000 of the 2.1 million people incarcerated in the nation’s prisons and jails.

The Vox.com article outlines these major points of The First Step Act:

• It makes the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 – which made the sentences for crack cocaine and powder cocaine more similar – retroactive, affecting some 2,600 federal inmates.

• It makes several changes to ease mandatory minimum sentences, for example by reducing the sentence for the “three strikes” rule to an automatic 25 years instead of life.

• It increases “good time credits” from 47 days to 54 days per year, which means well-behaved inmates can cut an additional week each year. This change is retroactive and

qualifies some 4,000 prisoners for early release.

• It allows inmates “earned time credits” for taking vocational and rehabilitative programs.

These credits allow early release to halfway houses or home confinement. The hope is that education programs will reduce the likelihood of the inmate commit additional crimes once released.

Charles Bolton and his wife, Linda, were indicted in March 2016 on five counts of attempted tax evasion and five counts of filing false tax returns and went to trial in September 2016 in the courtroom of U.S. District Court Judge Keith Starrett. Charles Bolton was convicted on four counts of attempted tax evasion and five counts of filing false tax returns and Linda Bolton was convicted on five counts of filing false tax returns.

The tax fraud case arose out of a 2014 investigation into whether Bolton, chief deputy since 1992, and others were stealing food from the Forrest County Juvenile and Adult Detention Center. Charges were not filed against Bolton as a result of the investigation, which was conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Mississippi State Auditor’s Office. However, statements about Charles Bolton’s participation in the thefts were included in the Pre-Sentencing Report (PSR) for the Boltons’ 2016 trial in federal district court and were the basis for the court’s decision that the food thefts were relevant conduct for purposes of sentencing and calculating loss and restitution amounts.

“Stolen food equals income,” Judge Starrett said when he sentenced Charles Bolton. “…Mr. [Alan] Harelson [and Mr. [Jerry Wayne] Woodland stood right there before me, under oath, and admitted to … how they had defrauded the Forrest County Jail for 12 years, beginning in 2002 and going all the way to 2014, and a lot of what they said involved the Boltons….

“But the story doesn’t end there. The court had access to and read, as the lawyers had access to and read, copies of interviews of a number of other people who were not interested in the case…. We’re not talking about one or two people. We’re not talking about people with an axe to grind. Their testimony did not just implicate the Boltons.

“The Pre-Sentencing Report, which was not objected to as to the factual statements at all, is replete with statements from witnesses and participants and people that worked at the jail and people that didn’t work at the jail about the food thefts that started in 2002 and continued until 2014….,” Starrett said, speaking directly to Bolton. “I believe what they said. There was a culture of corruption in the Forrest County Jail, and you knew it and you allowed it to go on…, and not only knew about it but participated in it for 10 years…. That is so troubling to me. This cannot be ignored. There are good people in Forrest County that deserve honest government.”

Bolton stated, “I did not do that.” Judge Starrett informed him that it was not his turn to talk.

Charles Bolton was sentenced to 43 months in prison with three years of supervised release and a $10,000 fine and Linda Bolton was sentenced to 30 months in prison with one year of supervised release and a $6,000 fine. Both were given responsibility for restitution of $145,849.78.

The restitution amount covers unpaid taxes for almost $28,500 in stolen food from the detention center and is based on a total loss amount of almost $146,000, as determined by the U.S. District Court; it also includes taxes owed on income the Boltons received from local attorney John Lee but hid by reporting it as loans.

The Boltons appealed the decision to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld the convictions and sentences in October 2018 but did rule that restitution payments of $1,000 monthly would not begin until the Boltons began their supervised release.

WOULLARD’S USE OF DISTRICT 4 REC FUNDS EXAMINED BY STATE AUDITOR

A source with first-hand knowledge told HPNM that the Office of the State Auditor began examining District 4 Supervisor Rod Woullard’s use of county funds as early this summer. The investigation involved funds spent from the District 4 Recreation Fund and focused on his use of those funds to employ Sandra Thompson.

Each Supervisor in Forrest County has a Recreation Fund, part of the General Fund, from which they direct monies to recreational projects or activities. HPNM has learned that Woullard used District 4 Recreation Funds to hire Thompson as a Special Project Officer for District 4 in June 2007. That’s prohibited by state law. “All employees of the county shall be employees of the county as a whole and not of any particular supervisor district.” (Mississippi State Code Ann., §19-2-9)

Various county records – from Board of Supervisors’ minutes to a workers’ compensation claim – clearly identify her as a Special Project Officer whose work centered on recreational programs and activities in District 4. District 4 Recreation Funds were used to pay her salary and travel, with the approval of the Board of Supervisors. Woullard is the only Forrest County supervisor who has paid an employee directly from Recreation Funds.

Ms. Thompson was hired initially at $12.00 an hour, but advanced quickly and received regular raises. Here’s what HPNM found:

June 21, 2007 $12.00

February 4, 2008 $13.75

April 4, 2008 $14.44

January 22, 2009 $16.35

County-wide Raise $17.85

August 11, 2014 $18.85

County-wide Raise 2016 $19.79

September 6, 2018 Voluntary Resignation

Ms. Thompson drove a county vehicle and used county-provided fuel. She worked from an office Woullard provided at The First Tee of The Pine Belt, in a facility he says he built in 2008 as District 4 Supervisor. Her job was to plan, direct and promote District 4 recreation programs. The source of funds used to build the charity’s facility are currently under investigation by HPNM.

Thompson was named Executive Director of First Tee of the Pine Belt in June 2007. This means that somehow she answered phones and handled other duties connected with the charity while holding down a full-time job as District 4’s Special Project Officer for recreation. First Tee of the Pine Belt, a non-profit that uses golf to build character and teach healthy choices to young people, is described online as the brainchild of Rod Woullard.

Outside employment is not forbidden by the county. This is what the Forrest County Employee Handbook says:

No employee may engage in employment which could cause a conflict of interest or use his County employment for personal gain. Outside employment must not interfere with performance of duties for Forrest County.

For the record, county attorney David Miller says that Ms. Thompson was a county employee, not a District 4 employee. However, here’s a description he provided of Ms. Thompson’s duties from a 2016 submission for workers’ compensation:

Ms. Thompson’s position as a Special Project Officer involves planning and directing various recreation programs for the citizens of District 4, facilitating the participation of the City of Hattiesburg, the Hattiesburg Public School District, and local non-profit entities in such programs, and communicating with the public regarding the nature and availability of such programs. Ms. Thompson’s work also involves various administrative and clerical tasks such as record-keeping, data collection, and reporting. (Parentheses added by HPNM)

Re-read the italicized words in the paragraph above and you’ll see that Ms. Thompson’s involvement with First Tee of the Pine Belt allows her to kill two birds with one stone: First Tee is a local non-profit entity and it benefits young people (presumably found at Hattiesburg Public School District).

WHO’S MINDING THE STORE?

HPNM has been told that board members consider Recreation Funds discretionary and generally respect their fellow supervisors’ decisions on how the funds are spent. Courteous, right? It’s lawful. We know that because a vote is taken. The net effect of this courtesy, though, is that supervisors give each other carte blanche in spending taxpayer money from Recreation Funds. That can amount to tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars over an period of years.

Consider Ms. Thompson’s salary. She started out in June 2007 making $24,960 a year. In roughly six months she received a salary bump and went to an annual salary of $28,600. Two months later, she again received a bump, to $30,035. Her 2009 raise brought her annual income to $34,008, and a subsequent county-wide raise increased it again, to $37,128. In 2014, Ms. Thompson received another pay increase; her salary then was $39,208. A 2016 county-wide raise brought her annual salary to $41,163.

Ms. Thompson voluntarily resigned in September 2018. The vehicle she drove, inexplicably, is parked at Supervisor Woullard’s residence, along with his county-provided vehicle.

HPNM has requested additional information from Forrest County, including copies of any reports or work products Ms. Thompson provided to the board and copies of any communications to or from the State Auditor’s Office regarding the administration of county Recreation Funds. HPNM’s investigation into Woullard’s use of District 4’s Recreation fund is ongoing and an update will be provided in the coming weeks.

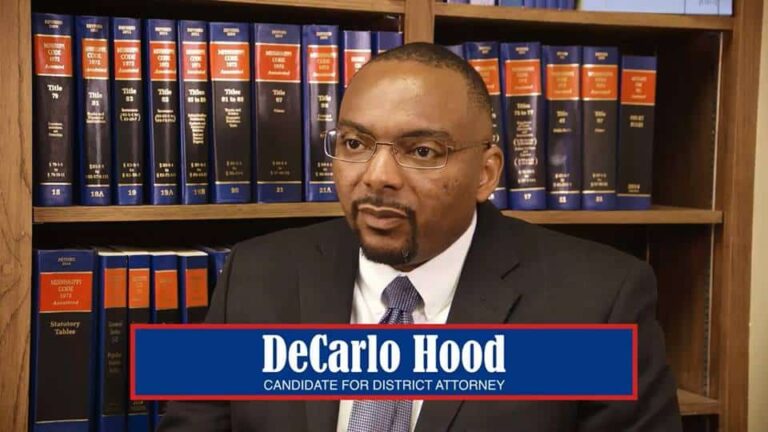

HOMESTEAD FILING RAISES QUESTIONS ABOUT DA CANDIDATE DECARLO HOOD’S RESIDENCY

(Specific addresses are not mentioned in this article. The Patriot also has redacted addresses and other sensitive information in attachments out of an abundance of respect for the public records laws, which protect that information for law enforcement, judges and court personnel.)

• The wife of Forrest County district attorney candidate DeCarlo Hood filed a false application for homestead exemption in Lamar County earlier this year. She was allowed to correct it a few months later, in accordance with state law.

• The new application for homestead exemption was necessary because ownership of the Lamar County house, located in Hattiesburg, was deeded to Hood’s wife in January 2018.

• Hood listed a rented apartment as his home address when he filed his qualifying papers to run for the office of Forrest County district attorney. However, he appeared to be staying with his wife at the Lamar County home during most of the month of March, when HPNM received a tip and conducted numerous spot checks.

• By April, the Lamar County house was put up for sale. Hood reportedly was made aware of the HPNM spot checks of the Lamar County property.

• Nothing in the above scenario, as described, is illegal. However, it raises questions, and perhaps eyebrows, as to the accuracy of the candidate’s campaign information and as to his intentions regarding his permanent residence. Full details are below.

Chaka Jackson, wife of Forrest County district attorney candidate DeCarlo Hood, filed a false application for homestead exemption application in Lamar County on February 8, 2019. When Ms. Jackson, also known as Chaka Jackson-Hood, applied for homestead exemption at the Lamar County Tax Assessor’s Office that day, she reportedly claimed that she and Hood are divorced, and that no vehicle is registered to her name. She signed the application for homestead exemption as Chaka Jackson.

Ms. Jackson was not asked that day to produce a copy of the divorce decree. However, the Hattiesburg Patriot’s investigation triggered an inquiry by the Lamar County Tax Assessor, who sent a letter to Ms. Jackson in late March notifying her of the discrepancies in her application and requesting a copy of the divorce paperwork.

Ms. Jackson is said to have been unable to provide that documentation. According to the Lamar County Tax Assessor’s Office, Ms. Jackson was allowed to file another application for homestead exemption in April, in accordance with state law. The corrected application states that she and Hood are separated.

Hood’s campaign website clearly states that he is married to Chaka Jackson-Hood and that they have two children. The Hattiesburg Patriot has been unable to locate Chancery Court records of any divorce action involving the couple but has learned that a car with a Lamar County tag is registered to Ms. Jackson at an address with a Hattiesburg post office box.

There’s More

Ms. Jackson had until April but filed for homestead exemption in February, the same month her husband qualified to run for Forrest County district attorney. To qualify, candidates for Forrest County district attorney must live in Forrest County. Historically, Hood and Chaka Jackson-Hood have not lived in Forrest County. Instead, they have lived within the Hattiesburg city limits, but in Lamar County.

Hood appears to have handled the residency hurdle. His campaign paperwork lists his address as an apartment in Forrest County. However, the Hattiesburg Patriot received a tip earlier this year that Hood had not spent much quality time at his new apartment and that his family continued to live at the Lamar County home.

HPNM confirmed this information during the last three weeks of March by conducting numerous late-night and early morning spot checks of the Lamar County home and by talking with neighbors at the Forrest County apartment.

Here’s a rough timeline:

January 10, 2018 DeCarlo Hood and his wife, Chaka Jackson, execute a quit claim deed for their Lamar County home, deeding the property to Chaka Jackson. The deed is filed January 16, 2018, with the Lamar County Chancery Clerk.

Summer 2018 Hood rents an apartment at a complex in Ward 1. His qualifying papers for the district attorney race list this apartment as his address.

February 8, 2019 Chaka Jackson files a new homestead exemption application for the property with the Lamar County Tax Office. In doing so, she states to a clerk that she is divorced, and that no vehicle is registered in her name. The clerk enters the information and Ms. Jackson then signs the application under penalty of perjury.

March 2019 HPNM talks to neighbors at the apartment complex who say they have seen DeCarlo Hood, but only a rare handful of times. One has noticed children there.

March 2019 City water bills for the property that was quit-claimed to Ms. Jackson in January 2018 are still listed in Hood’s name.

March 2019 During the last three weeks of the month, Hood’s county-provided vehicle is parked at the Lamar County home each time HPNM conducts a late-night or early-morning spot check.

April 2019 Chaka Jackson files a corrected homestead exemption application to reflect that she and Hood are separated. This action puts Hood’s name back on the homestead as non-occupying joint owner and spouse.

Early April 2019 A For Sale by Owner sign appears in the yard of the Lamar County home.

October 2019 The For Sale by Owner sign remains in the yard of the Lamar County home.

DeCarlo Hood is well within the bounds of Mississippi election law in renting a Ward 1 apartment and establishing permanent residency in Forrest County so that he can campaign for the office of Forrest County District Attorney. However, some actions he and/or Chaka Jackson have taken could be perceived as confusing or possibly even deceptive.

- Why did the Hood’s execute that quit claim deed and put the house in Ms. Jackson’s name?

- Was DeCarlo Hood aware of his wife’s intention to file a false application for homestead exemption?

- If the two are married, as Hood states on his campaign web site, why didn’t Ms. Jackson and the children move with Hood last summer to Forrest County?

- Does Hood intend to continue living in Forrest County regardless of the outcome of the district attorney election? In other words, has he established a permanent residence in Forrest County?

We can’t answer any of these questions. The best we can do is examine the law and Attorney General opinions regarding residency requirements for candidates and homestead exemptions.

To Qualify for District Attorney…

The following requirements for candidates for district attorney are taken directly from the Secretary of State’s website at the candidate qualifications page (click here to go to the site https://www.sos.ms.gov/Elections-Voting/Documents/Qualifications):

DISTRICT ATTORNEY

Qualifications: A qualified elector of the district and a practicing attorney admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of Mississippi for two years. Miss. Code Ann. §25‐31‐1.

Political Party Candidates: $250 paid to the appropriate state party executive committee.

Independent Candidates: $250 paid to the Secretary of State’s Office, and petition filed with the Secretary of State containing signatures of not less than 100 qualified electors of district.

State law defines a qualified elector as a person whose name the circuit clerk has placed on the electronic voter roll as “properly registered and qualified to vote” and who is a resident of the county or municipal school district. (The full definition is at Miss. Code Ann. §37-65-123.)

Ultimately, it’s the Forrest County Election Commission’s responsibility to decide whether DeCarlo Hood meets residency requirements. Here are some key court cases and AG opinions that address questions about candidates, where they live, and their eligibility to run for public office:

Court Cases on Residency

1. In election law, residency and domicile are the same. Once established, a legitimate residence continues until it’s abandoned in favor of another with no intent to return. Hubbard v. McKey, 193 So.2d 129 (Miss. 1966)

2. A candidate’s filing for homestead exemption creates a “strong but rebuttable presumption” that the property for which the homestead exemption is filed is the candidate’s residence for election purposes. Hinds County Election Commission v. Brinston, 671 So.2d 667 (Miss.1966)

3. Filing for homestead exemption conclusively establishes domicile for electoral purposes, even if circumstances indicate the existence of ties to other counties. Gadd v. Thompson, 517 So.2d 576 (1987); Hollowell v. Vandevender, 358 So.2d 1328 (1978).

4. Intent is the foundation of residency and can be established by physical presence, declaration of intent, and all relevant facts and circumstances. Of these, declarations of the individual are most important. If there is no declaration of intent, and no acts demonstrating a contrary intent, long-continued residency is almost “unavoidably conclusive” in deciding residency. Ownership of personal or real property is not necessary to establish permanent residency. Stubbs v. Stubbs 211 So.2d 821 (1968).

5. The best evidence of domicile is actual residence, not just the fact of residence. A person can explain staying at another place and rebut the presumption of residence. In determining residence, little weight is merited for statements of intent that are in conflict with the facts. Cheek v. Fortune, 341 F.Supp 729 (N.D.Miss., 1972).

6. The essential elements of domicile are residence and the purpose to make the residence a home. Texas v. Florida, 306 U.S. 398, 83 L.Ed. 817 (1939).

7. The intention to make a home must be unqualified and not conditioned on the occurrence of a future event. Jones v. State, 207 Miss. 208, 42 So.2d 123 (1949).

Attorney General Opinions on Residency

1. The appropriate election commission is responsible for making factual determinations on questions of residency. The commission should decide residency on a case-by-case basis and in accordance with guidelines (listed within the opinion) established by the courts. (Conaway et.al., 9-20-89)

2. When a person files for homestead exemption, his or her application establishes residency in that county conclusively and indefinitely for electoral purposes. A person who has filed for homestead exemption in one county may establish residence and become a candidate for public office in another county. Determination of residency is a question of fact to be made by the election commissioners. (Gamble, 9-13-95)

3. Once residency is established, it continues until the [candidate] moves elsewhere with the intent to remain at the new residence and abandons the old domicile with no intent to return. However, the individual’s expressed intent must be viewed in light of the actual situation. In determining residency, statements of intent are entitled to little weight when in conflict with the facts. (Mickens, 6-15-95) and (Shirley, 7-7-95)

4. If the election commission finds that an individual satisfies the residency requirements as a matter of fact, the commission must include that name upon the ballot. The municipal election commission is authorized to inquire into the residency of a candidate prior to the printing of the ballots. If a candidate does not satisfy the residency requirement, then the burden shifts to the candidate to negate the finding of the commission. (Norwood, 9-5-97)

5. Candidates must meet all qualifications for the office they seek at the time the election officials meet to rule on candidate qualifications. (Evans, 4-19-95)

6. A qualified elector seeking public office must meet all eligibility requirements,

subject to no contingencies, at the time such candidate is elected, not by the qualifying

deadline. (Kihyet, 10-31-95)

7. A candidate for the office of county supervisor must be a resident of the district he seeks to serve. (Salmon, 6-17-91) (Candidates for district attorney meet the same qualifications as candidates for county offices.)

8. Residency of a potential candidate for municipal office is a question of fact that must be determined by the appropriate election commission or, in case of a primary, the appropriate party executive committee. (Davies, 2-23-01)

Homestead Exemption 101

The application for homestead exemption must be filed between January 1 and April 1 each year. If granted, it gives taxpayers a break on all ad valorem taxes assessed to the property, limited to the first $7,500 of the assessed value and to $300 in actual exempted taxes. Once filed, the application does not have to be re-filed unless there is a status change, for example death, divorce, a sale of property or an addition of property.

The law states that the application must be complete, true, and correct. Exemptions can be disallowed for many reasons. Here are some reasons, taken from Chapter 1 of the Mississippi Administrative Code:

3. Applicant is separated, does not have custody of minor children and does not live in

the home at the time of separation. 27-33-13 (c) & (d)

7. Applicant is not defined as the head of a family. 27-33-13 and 27-33-19

23. Applicant does not occupy the property as his primary home. 27-33-19 and 27- 33-21

25. Any property and/or dwelling that is occupied under an agreement to buy or under a

conditional sale is not eligible. 27-33-21 (d)

26. Property that is rented or is available for rent is not eligible. 27-33-21 (a) & (g)

39. Valid application is not on file. 27-33-31 (a)

40. Applicant has made a fraudulent application. 27-33-31 (q) and 27-33-41 (c)

42. Applicant and spouse are not actually and legally living together. 27-33-19 (c)

Penalties are outlined in Chapter 8 of the Mississippi Administrative Code:

1. Any person who swears under oath to the truthfulness of an application which is found to

contain a false statement is guilty of perjury.

2. Any person who knowingly makes a false claim for exemption or a false statement on the

application or omits a material fact on the application in order to obtain an exemption is guilty

of a misdemeanor. Anyone who assists another in preparing a false claim for exemption is also guilty of a misdemeanor. If the person is convicted, the punishment includes a fine of not more than five hundred dollars ($500) or six (6) months imprisonment. If an exemption is obtained under a false claim, the person obtaining such an exemption is liable for double the amount of taxes lost.

3. In addition to the above, anyone who submits a fraudulent application in violation of Section 27-33-31, Mississippi Code Annotated, is guilty of a felony and if convicted could face a fine of not more than $5,000 or a prison term of not more than two years, or both.

Key Court and Attorney General decisions on Homestead Exemption

• A board of supervisors may not allow homestead exemption for a taxpayer who fails to comply with Section 27-33-31 of the Mississippi Code of 1972. (Williams, 7-25-97, citing consistency with Welch, 4-16-94).

• The filing of a homestead exemption conclusively establishes domicile for electoral purposes

in the county of filing, even if certain ties to other counties still exist. In Gadd v. Thompson,

517 So.2d 576, 579 (Miss.1987), the Mississippi Supreme Court said that as a matter of law, if an individual has filed for homestead exemption in a particular county he may not legally be a qualified elector (registered voter) in another county. Therefore, filing for homestead exemption conclusively determines residency for voting purposes. Once a county election commission determines that a person whose name appears on the voter registration records has filed for homestead exemption in another county, it is obligated to remove that name from its records for state and local elections.

The National Voter Registration Act of 1993, better known as the Motor Voter Law,

became effective in Mississippi on January 1, 1995, and has a specific procedure that must

be followed before a voter can be disqualified from voting in federal elections based on

residence.

Section 97–13–25 of the Mississippi Code, Rev. 1994, provides that any person who knowingly registers to vote when not entitled to be registered, or who registers to vote under a false name or in a district other than the one in which he or she lives shall be imprisoned in the penitentiary for a term not to exceed ten years, if convicted. (Ward, 3-28-95)

• In Gadd v. Thompson, 517 So. 2d 576, 579 (Miss. 1987), the Mississippi Supreme Court held that the filing of homestead exemption conclusively establishes domicile for electoral purposes in the county of filing, regardless of whether ties to other counties still exist. (Also, Ward, 3-28-95) Whether a candidate meets residency requirements is a question of fact to be determined by the municipal election commission. However, the Gadd case clearly states

that where an individual files homestead exemption establishes his domicile for all electoral

purposes, including running for office and voting. (Hood, 6-5-98)

Click on this link for complete information on Homestead Exemptions.

Documents used to support the facts in this article.decarlo-hood

Lamar County candidates violate campaign finance laws

In Lamar County, 21 candidates or former candidates for public office have violated Mississippi law by failing to file mandatory campaign financial disclosure reports or by filing them after the deadline. All face financial penalties and/or prosecution if the Ethics Commission enforces state law.

Two candidates for state office on Lamar County’s ballot for the November 5 election failed to file the campaign financial disclosure reports that were due in October. Two additional candidates for state office filed the required reports but did so after the 5 p.m. October 10 deadline, as did a local candidate for Chancery Clerk. The remaining 16 are former candidates for county office who were defeated in the primaries.

However, Lamar County’s ballot includes two candidates for state office who live elsewhere in Mississippi and have not submitted the required financial reports, bringing the total to 23

candidates and former candidates who are in arrears with their campaign financial disclosure reports. They are:

1. Ken Morgan (R) – candidate for State Representative, District 100 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

2. Brandon Terrion Rue (D) – candidate from Meridian for State Representative, District 102 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

3. Jansen Owen (R) – candidate for State Representative, District 106 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

4. Addie Lee Green (D) – candidate from Bolton for State Treasurer – has not filed a periodic report for October.

5. Melissa Brezeale Love (R) – candidate for Chancery Clerk – has not filed a periodic report for October.

6. Cheree Sanders (R) – candidate for Chancery Clerk – has not filed a periodic report for October.

7. Anna E. Miller (R) – candidate for Coroner – has not filed a periodic report for October.

8. Hunter Andrews (R) – candidate for Surveyor – has not filed a periodic report for October.

9. Jeremy Tynes (R) – candidate for Surveyor – has not filed a periodic report for June, July 10, July 30 or October.

10. Larry Bracey (R) – candidate for Supervisor, District 3 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

11. Robert Hedgepeth (R) – candidate for Supervisor, District 3 – has not filed a periodic report for July 30 or for October.

12. Joshua Kent Grantman (R) – candidate for Supervisor, District 4 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

13. Brian McPhail (R) – candidate for Supervisor, District 4 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

14. Eddie Thaggard (R) – candidate for Supervisor, District 4 – has not filed a periodic report for July or October.

15. Jon Mark Herrington (R) – candidate for Supervisor, District 5 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

16. Dearl Head (R) – candidate for Constable, District 1- has not filed a periodic report for October.

17. Johnny Whitehead (R) – candidate for Constable, District 2 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

18. Jimmy R. Daughdrill, Sr. (R) – candidate for Constable, District 3 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

19. Abner Keith (R) – candidate for Constable, District 3 – has not filed a periodic report for October.

20. Lyn Thompson (R) – candidate for Constable, District 3 – has not filed a periodic report for July or October.

Also:

21. Phillip D. Carlisle (R) – candidate for Chancery Clerk – filed a periodic report for October but not by the 5 p.m., October 10, 2019, deadline.

22. Kent McCarty (R) – candidate for State Representative, District 101 – filed a periodic report for October but not by the 5 p.m., October 10, 2019, deadline.

23. John A. Polk (R) – candidate for State Senator, District 44 – filed a periodic report for October but not by the 5 p.m., October 10, 2019, deadline.

THE STATE’S REQUIREMENTS

All office holders and candidates were required to file an annual campaign finance report by January 31, 2019, for the 2018 calendar year, as well as periodic follow-up reports throughout the year according to a schedule provided by the Secretary of State.

The only exceptions are office holders and candidates who have filed termination reports. A politician or candidate who files a termination report states that he or she will no longer accept contributions or spend funds and that his or her campaign has no debt or obligations.

A candidate who withdraws, is disqualified, or loses the race still must submit campaign finance reports until a termination report is filed.

You’ll find campaign finance laws set forth in the Mississippi State Code Ann., beginning at Section 23-15-801. The Secretary of State’s Office has made it easy for politicians to comply and the public to understand, though, by publishing a handbook online on Mississippi campaign finance law. It’s called the Guide to Campaign Finance in Mississippi: For Candidates and Political Committees and is posted online at the Secretary of State’s website.

Under our current campaign finance laws, the Secretary of State is responsible for providing the necessary forms, for promoting rules and regulations, for collecting reports and statements and for making them available for public inspection. (Mississippi State Code Ann., Section 23-15- 815)

The Secretary of State is required by law to compile a list of all candidates for the Legislature and other statewide office who do not file campaign finance reports on time, and to provide that list to the state Ethics Commission, which in turn can bring a mandamus or take other disciplinary action. The Secretary of State also is required to distribute the list to members of the Mississippi Press Association. (Mississippi State Code Ann., Section 23-15-817)

Enforcement is left to the Ethics Commission.

PENALTIES

State law says that once a campaign finance report is ten days late, the Ethics Commission shall assess the violator a penalty of $50 for each day or part of a day until the report is submitted.

There’s a maximum of 10 days, so delinquency can cost as much as $500 per report.

Legally, “shall” means there is no wiggle room. However, state law also provides the Ethics Commission discretion to waive all or part of the fine if it determines the existence of “unforeseeable mitigating circumstances.” The health of the candidate would be an acceptable excuse; not having received a notice of failure to file the report from the Secretary of State is not an acceptable excuse. Politicians who file the report and pay the fine within 10 days of receiving notice from the Secretary of State are considered in compliance with the law, but paying the fine without filing the report? Not so much. (Mississippi Code Ann. Section 23-15-813)

This same section of law outlines the procedure for non-payment of fines that have not been waived. In that case, the candidate or politician is scheduled for an administrative hearing; there is an appeals process for the hearing. Ultimately, the Attorney General may opt to prosecute to recover the assessed penalties.

SANCTIONS (OR, WHAT’S IN A NAME?)

Beyond the penalties, violators of campaign finance laws can incur sanctions, which are, in a word, more penalties. Here they are:

1. Willful violators shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and, if convicted, shall incur a fine of up to $3,000.00 or prison of six months, or both.

2. The violator may be compelled to file the necessary report by a mandamus brought by the state Ethics Commission.

3. A candidate who has not filed his or her required campaign finance reports shall not be certified as nominated for election or as elected to office until he or she files all reports due as of the date of certification.

4. A candidate who has not filed his or her required campaign finance reports shall not receive any salary or other remuneration until he or she files the reports due as of the date the salary is to be paid.

5. These sanctions do not apply if the candidate fails to file his or her campaign finance report on time but files a complete report later. (Mississippi Code Section 23-15-811)

The Hattiesburg Patriot has submitted a request to the Ethics Commission for information as to whether and/or how campaign finance laws are enforced at the local level.