Melvin Jones, a 64-year-old native of Cleveland, was in his 30s when he was diagnosed with diabetes. He knew he was at an increased risk because of his family history.

In 2013, at 54 years old, Jones had two toes on his right foot removed and would later lose the big toe on his left foot. He didn’t know it then, but he had peripheral artery disease, or PAD, a condition where plaque builds up in peripheral arteries – those that do not supply blood to the heart or brain – and restricts circulation. Without treatment, a patient will continue to need further amputations and will die young.

One doctor told Jones he would likely need to amputate his entire foot – but Jones, whose condition made him retire early from his job at Baxter Pharmaceuticals, was resolved not to let that happen.

“I thought ‘I don’t want that,’ and me and the doctor were through,” Jones said. “It would have changed my life. I already can’t drive my truck no more.”

But many diabetics in rural Mississippi don’t have access to the care Jones went on to receive to avoid further amputations. Diabetes and the cardiovascular problems it causes are often asymptomatic at first, or symptoms are obscure. A lack of specialists coupled with some of the lowest social determinants in the country leave regions like the Delta prone to late detection of diabetes and a high rate of amputations.

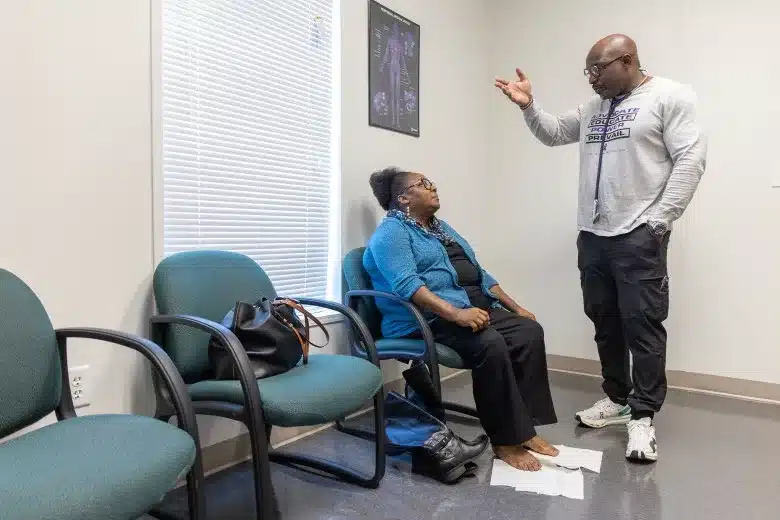

Now, Jones goes to cardiologist Dr. Foluso Fakorede’s Cleveland clinic, Cardiovascular Solutions of Central Mississippi, for regular wound care from a nurse practitioner who travels to the clinic every Thursday from Oxford.

His life is different now, but he’s thankful he can still move around and hasn’t had to undergo a major amputation, which, for legs, is characterized as any cut above the ankle joint.

Mississippi is the only state with every county represented in what is called the “diabetes belt” of the U.S., which spans an upward arc from the deep South to Appalachian states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Fakorede said academic institutions should be investing in the region through medical research, but it’s not an attractive market.

“I’ll make the argument that it should be,” he said. “Because these people were never given the chance to catch up. And now we’ve left them to suffer in isolation and in pain.”

With 14.8% of its adults diagnosed with the disease, Mississippi is second only to West Virginia in prevalence.

Uncontrolled diabetes, which runs rampant in rural and underserved areas, can lead to blindness, kidney failure, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart attacks, strokes and gangrene.

Mississippi, one of 10 states that has not expanded Medicaid, is the fifth highest uninsured state. In Bolivar County and several other Delta counties, at least one in five residents have medical debt in collections.

About one in three diabetics over the age of 50 will develop PAD, which often goes undiagnosed and untreated in medical care deserts like the Delta.

When it is caught, doctors often have an “amputation-first” mentality, which results in the loss of limbs and early mortality – despite the fact that a procedure exists to clean out the arteries of a PAD patient and restore blood flow to extremities.

Within five years of an amputation, diabetics stand a good chance of being dead. Nationally, Black patients are four times more likely to suffer diabetes-related amputations than white patients.

“It’s a death sentence,” Fakorede said, “and it’s very often preventable.”

The procedure capable of decreasing a PAD patient’s odds of amputation by 90% is called an angiogram, an invasive diagnostic imaging test that detects arterial blockages. Revascularization is the therapeutic procedure that cleans out those arterial blockages.

Jones received five angiograms and revascularization procedures in both his legs over the course of the last two years.

The number of angiograms a diabetic patient with PAD will need depends on a number of risk factors such as age, race, hypertension, heart conditions and habits such as diet and tobacco use.

In the U.S., more than half of patients never receive an angiogram or revascularization procedure before a major amputation.

At his Delta clinic, Fakorede, the only cardiologist in Bolivar County, estimates that the number of amputees who never had an angiogram is close to 90%.

Fakorede, who was born in Nigeria and spent his teenage and young adult life in New Jersey, struggled to justify moving to Mississippi and opening his own clinic. He knew nothing about the place and had never operated his own business. But when he saw how great the need was in the Delta for a procedure he was skilled at, he knew his mind was made up.

“You walk through Walmart or Kroger here,” Fakorede said, “and I promise you you’ll see someone who has had a limb taken off or a dialysis catheter around their neck.”

In the end, Fakorede said the Delta proved to be far more similar to his hometown in Nigeria than he thought. They are regions that, for the majority of residents, reflect nothing of their country’s wealth – despite the rich resources they provide that contribute to that wealth.

“That is actually what made me stay – that similarity,” he said.

In the Delta, Fakorede explained, there are a number of socioeconomic factors that contribute to what he calls “the perfect storm” and leave people at a greater risk of chronic and life-threatening conditions.

Studies have shown that the body’s inflammatory response to chronic stressors like poverty, food deserts and unemployment – all of which pervade the Delta – can accelerate diseases like PAD.

Fakorede believes that a large part of the problem is inadequate screening measures. The United States Preventive Services Taskforce, or USPSTF, is the governing body that doctors look to for recommendations on who to screen for which conditions.

The USPSTF has not endorsed a screening for PAD, despite the fact that the five-year mortality for undiagnosed or untreated PAD patients is higher than that of breast cancer and prostate cancer, and studies have shown minorities are disproportionately affected.

“That is atrocious,” Fakorede said. “These patients have existed for decades. We know that this disease is destroying them because it’s taking them out of the workforce. It’s taking them out of their homes. They’re ending up in caskets early on.”

Meanwhile, Ozempic shortages are sweeping the nation as doctors prescribe the FDA-approved, weekly Type 2 diabetes medication to patients without diabetes for weight loss.

In Mississippi, nurse practitioner KC Arnold, director of the Ocean Springs Diabetes Center, witnesses the shortage daily.

“Every single day I’m getting a call: ‘hey, my pharmacy can’t get this,’” Arnold said. “In all my years of helping people with diabetes, this has been the biggest challenge for me to help people get what they need.”

Arnold’s facility is nurse practitioner owned and run – a rarity in Mississippi, where restrictive and expensive collaboration agreements limit the freedom with which nurse practitioners can operate.

Ozempic has a weight-loss version called Wegovy, but it isn’t covered by Medicare, so doctors will sometimes prescribe Ozempic in its place. The Mississippi Board of Nursing has guidelines that prohibit nurse practitioners from prescribing the weight loss drugs off label. But that rule doesn’t apply to doctors.

Arnold says she supports insurance companies covering a drug that addresses obesity. But until that happens, doctors shouldn’t be prescribing Ozempic to patients for weight loss.

“I can’t get the medicine for my patients with Type 2 diabetes,” she said. “Insurance needs to change to help people with weight – I’m all for that – but right now my patients with diabetes need medicine they’re not getting.”

And the drug isn’t just prescribed to people with diagnosed obesity. Chelsea Handler, a comedian and host of the 2023 Critics Choice Awards, joked that “everyone’s on Ozempic” in Hollywood.

Many insurance companies don’t cover drugs prescribed off label, but those who can afford it are paying premiums out of pocket.

“You know who ain’t getting it?” Fakorede said. “We ain’t getting it here in the Delta. There are people who are not even diabetic who are getting it in the Upper East Side in New York. Socioeconomic status matters.”

Mississippi’s alarming rate of diabetes plays a significant role in another of the state’s abysmal health statistics: leading the country in infant and maternal mortality.

Pregnancy tends to highlight the socioeconomic disparities of diabetes since some women receive Medicaid coverage for the first time during pregnancy, according to maternal-fetal specialist Dr. Sarah Novotny.

“Often, pregnancy is the first time women have access to health care insurance,” Novotny, who serves as division director of maternal-fetal medicine at University of Mississippi Medical Center, said. “So, a lot of times patients are coming into pregnancy with very poorly controlled diabetes because they didn’t have access to pre-pregnancy care.”

In pregnancy, diabetes can be separated into two categories: women who already had diabetes, whether it be Type 1 or Type 2, and then became pregnant, versus those who developed gestational diabetes during pregnancy.

Women who have preexisting diabetes and become pregnant are at risk of developing vascular problems, high blood pressure, renal problems and retinopathy. Gestational diabetes doesn’t carry the same risks for the mother. Both conditions carry increased risks such as abnormal growth and birth defects for babies.

Women who develop gestational diabetes carry a 50% risk of developing Type 2 diabetes later in life.

Managing diabetes before conception would go a long way in mitigating the state’s maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity rates, according to Novotny. But at the very least, recognizing and diagnosing diabetes during pregnancy can serve as an opportunity for previously uninsured or underinsured women to improve their quality of life.

In the last three decades, despite all the technological and medical advancements that have been made, diabetics in minority populations have seen worse outcomes.

Turning those statistics around would mean prioritizing tackling inequities in health care and recognizing places like the Delta as meccas for research, according to Fakorede.

“We need to be collaborators,” he said. “We need to be hope dealers. We need to be disruptive in terms of using our positive thinking to address some of the systemic inequities that have plagued these people and this region for decades.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Read original article by clicking here.